Sunset Boulevard

*****

For optimal display, please read this on a desktop/laptop, not a mobile. Thank you.

*****

Sunset Boulevard

5 stars out of 5 (Masterpiece)

Director and Co-Writer : Billy Wilder

Co-Writers : Charles Brackett, D M Marshman Jr

Producer : Paramount Pictures

Cast : Gloria Swanson, Willian Holden, Eric Von Stroheim, Nancy Olsen

English , 1950

Very few writer-directors even in the history of modern Hollywood have had the gumption to pull off the the kind of darkly powerful mainstream movies that Billy Wilder became famous for making in the 1940s and '50s. In such cases, your producer will only back you when he feels that even his commercial bone has to sometimes give way to the marrow of pure talent. After the sunnily sepulchral magnificence of 'Sunset Boulevard' , Wilder made "Ace In The Hole" (1951) whose cynical dust seeps into the soul the deepest...and then maybe he couldn't take it any more, starting a late career comedic spree that truncated the intensifying greatness. But Sunset Boulevard is him at his zenith - a dirge about Hollywood in kaleidoscopic monochrome - plucking on multiple strings, deftly weaving through a succession of moods until the tragedy that blooms brighter than ever at the end isn't quite a Greek one , it's the exclusive exquisite hell of a Californian nightmare.

"You don't have the eat the whole jar of caviar to know it's good", says Clifton Lawrence in Sidney Sheldon's seminal "Stranger In The Mirror". The first shot of Sunset Boulevard, promises of the focus to come, panning from a pavement over which the film's title is inscribed, to glide on, slowly and continuously, over the asphalt against which the opening credits roll, and over which presumably both wannabes and ageing have-beens get dragged over.

A young film-writer, Joseph Gillis (embodied by William Holden), is in financial dire straits, his rent unpaid for three months, his pleas for help to agents and producers falling on slickly deaf ears, with hired musclemen out to confiscate his car for unresolved debts. Echoes from Wilder's preceding works pepper the start. The dialogue and mise en scene richly recall glorious pulp fiction - Wilder had worked with Raymond Chandler in the pulpily magnificent "Double Indemnity" a few years earlier. A shot from the exterior, gliding into the upper windows of a building that houses Gillis's apartment reprises a similar one in "Lost Weekend".

Escaping from the henchmen, he stumbles into the crumbling, commodious estate of Hollywood's Miss Havisham. There hides and seethes, a middle-aged yesteryear Hollywood superstar Norma Desmond (played by Gloria Swanson, herself a big star in the 1920s). Two decades ago she had the whole tinseltown eating out of her hands, but now she refuses to accept retirement. Alone and drunk on the ghosts of that fantastic past, she is doted upon by a mysteriously asssiduous butler (enacted by Eric Von Stroheim - a famous founding director and filmstar himself). Norma persudes Gillis to stay, asking him to fine-tune a come-back (Norma : "I hate that word !") script she's writing to essay her glorious return. He needs to survive, and she needs someone who can further her delusion and even someone whom she can manipulate romantically. A young lady (essayed with utterly guileless charm by Nancy Olson) comes along later, vying for Gillis's attention... and he soon realizes what sort of arcing odysseys Sunset Boulevard can take you on.

Pic compendiates the best of Wilder's serious cinema. You see the sense of confident clear framing and smooth dynamism that is the filmic equivalent of being in luxury lodgings. The famous reply Norma gives when told "You used to big" is smoothly covered in a shot that swiftly moves from medium-distance confab to marquee close-up ; Gilles goes to a see a producer for help, and the shot starts not with commonplace back-'n'-forth cutting, but with a focus on the cigar-lighting prosperous producer and then drawing back to reveal Gillis across the gulf on the other side of the table. The sharp nip and juiciness of dialogue never subsides - it is not highly sophisticated but 'tis healthy corn of the highest caliber. The mature steadily evolving screenplay does not mock your intelligence - note how the tone implacably shifts when a young lady visits a house late in the story (inverted years later in 'The Apartment'). Even in spoken style and mood as a unusual reflection of temperature, one can sense here a dry crackly crisp sense of Americanness - also evident in 'Lost Weekend' and 'Ace in the Hole' - as if you were walking by on a hot American summer day.

Sometimes that auteuristic confidence takes too much risks. Death is revealed at the start, as though Wilder dares to say 'Take this - I have shown you the unexpected ending right at the start', unshakeable in his belief that the moment-to-moment gravitas of the story will carry it through. It's a brave decision, but alas it upends what could have been a shocking turn of events at the end (cf. 'American Beauty').

But that's only a minor gripe, and one of the joys of a superior screenplay like this, is how they richly populate their nooks and crannies where lesser works gape hollow between main scenes. As Gillis escapes the hoods, he drives by the cobbler and observes that the cobbler never judges you, he "just looks at your heels and knows the score!". Hollywood is serially skewered at the start with darting one-liners, culminating with a producer himself taking the hit - when he hears how another producer myopically let go of "Gone with The Wind", he confesses, "No, that was me - I said, 'Who wants to see a film about the civil war ?!"

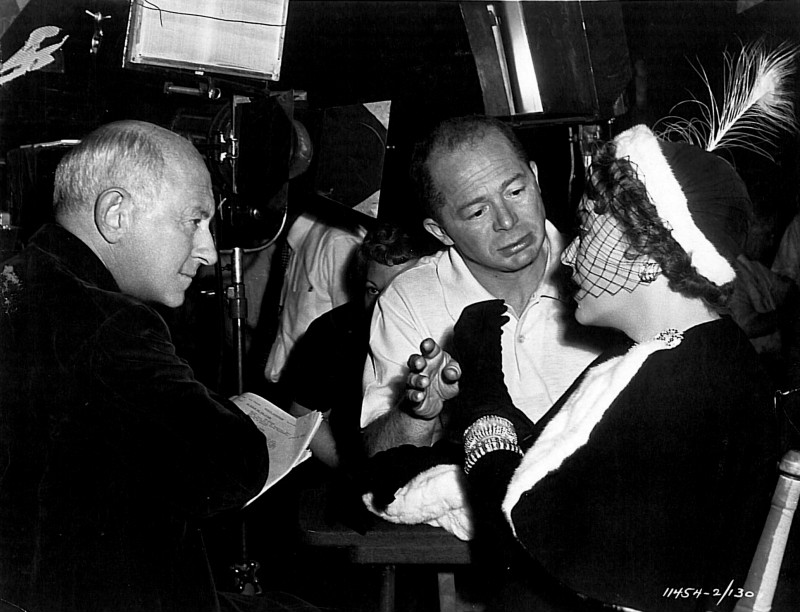

None of the film's principals are introduced in movie-star style. Wilder reserves that honour for the iconic real life director Cecil B DeMille who plays himself in the movie. A phone call to the stage-set that a visitor is coming in to see him, has not one but two point of verbal relays , with only the third informed man in the chain of command, being able to go up to the venerable auteur himself to convey the message. We see a shot of DeMille from the back and then he turns sideways to reveal his face, surrounded as this cine monarch is by his courtiers - a subtly superb sequence overall.

(L) to (R) : Cecil B. DeMille, Billy Wilder, Gloria Swanson

Norma comes to see him, palpitating under a misapprehension, hoping he'll make a big picture again with her, so that they will relive the glamorous achievements of the several previous films they'd made two decades ago. DeMille, unlike some top directors, is flawlessly natural and subtly nuanced when it comes to emoting as an actor (he could easily embody a tough but wise and kind senior doctor), holding Norma's hand and being gently pampering towards her from start to finish, the scene doubly great because of their famous real-life director-heroine interactions from 1919 to 1921.

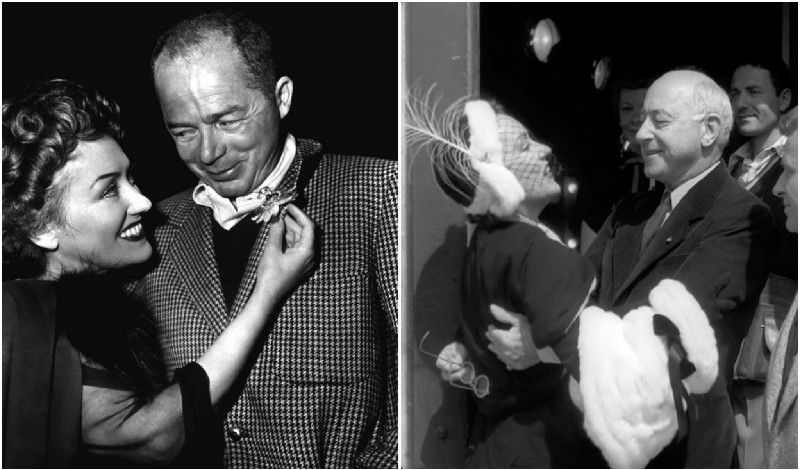

(L) : Gloria Swanson, Billy Wilder (R) : G S, Cecil B. DeMille

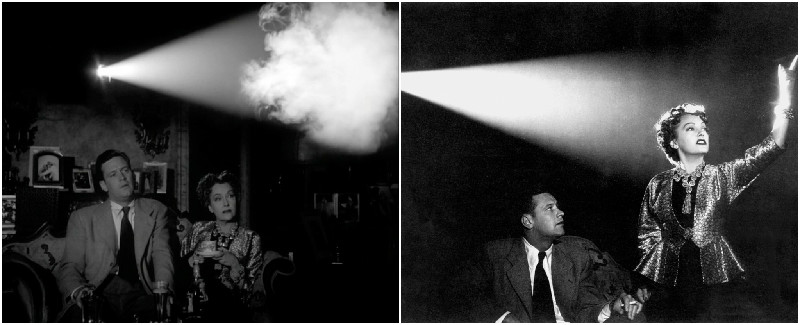

That sequence sports another beautiful moment, when a lighting man recognizes her and shines the spotlight upon her. It takes that artificial sun to make people notice her - murmurs spread - "Look ! , There's Ms.Desmond ! " and the decades collapse in nostalgia as film personnel mill around this superstar from the past. "Put that light back where it belongs", Mr.DeMille firmly says, returning to disburse order on the set, the only one time that he is unkind in his words or behaviour to Norma who seems to have missed the jab. Her complacent delusion swirls unchecked - "I don't care about the money!" she remarks, when DeMille suggests it is going to be an expensive film, as though the producer is going to have the money raining down from the skies.

In the film parlance of certain circles, there's the term "double acting", popular in the 60s and 70s, of a single actor portraying two separate characters in the same film. Gloria Swanson plays only one character here but she "double-acts". Her face contorts, eyes arc, cheeks tense, lips leer, hands are upflung in painting the grotesquerie of her tortured soul - the words merely reflect the Sturm und Drang already implicit in her expression. Swanson of course acts not just perfectly but also with time-transcending greatness - the role requires her to ham it up and she does so gloriously. It's a brand of exaggerated acting that artists were obliged to pull off in the centuries of stage dramas where quiet subtleties would be lost on physically far-away audiences, and in silent pictures perhaps where spoken dialogue was denied, but Norma keeps on doing this in her real life (interestingly, the one film reel we see of her youthful self shows tenderly subdued acting).

Her middle-aged face shows vestiges of a sharp-featured beauty, and the voice though husky, has a core of constant steel, now corroded by hubristic obssession. Her mansion in which she exiles herself, afraid to venture out into the real world, is a large high-ceilinged aristocratic affair, just outside of which the grounds and pool and driveway lie in disrepair, just like how the disorder swirls around her passably kempt demeanour. Her personality ricochets between borderline to narcissictic to suicidal, with dangerous instability being the only constant. When Gillis honestly tells her that she is the only person in that whole town who was kind to him, we eventually figure out what genre of kindness it actually was. Arriving after decades at the Paramount Pictures gate, she sees that the guard won't let her in, but an older one fondly recognizes her and gives access, but she does not say one word of "Hi! or "How are you?" or a warm smile or even a tip - there's just "Open the gate", and "Teach your friend some manners".

You may want to sympathize with her when she is in her piteous throes, but when Holden nee Gillis flings his hands in superbly conveyed utter frustration and declares, "There's nothing wrong in being 50, not unless you insist on being 25", and the lady cannot internalize the wisdom of his words, you wonder not just about the depth of unfulfilled desire in this fifty year old lady, but also about whether there was any hint of this madness when she was twenty-five years old.

Not for nothing was William Holden a leading star for two decades from the 1950s. At first his Joseph Gillis seems a run-of-the-mill character haplessly negotiating his pitiable fate but the role acquires more complexity as Gillis weighs how much longer he can subsist under a doting older lady. You can see the tension and the weight of decision simmering just under the skin of his face, silently erupting in a cold shower of dead smiles and complex manouevering when he eventually shows a visitor his deluxe current lodgings.

Great works automatically inspire weak imposters, but a landmark like Sunset Boulevard inspires certain segments in works that are great by themselves. Mario Puzo's iconic novel "The Godfather" has an floridly explicit sequence of a dethroned Hollywood queen similarly watching projected movies in her house while taking it much lower by sexually satisfying herself in the basest of ways with a younger man. Sidney Sheldon's magnum opus "The Stranger In The Mirror" has a sub-plot about a yesteryear founding father of the industry who now roils in pitiable shame and rage, desperate for a Hollywood that is gone even before the wind.

At one point in the finale, I had a faint doubt whether Sunset Boulevard was truly a masterpiece, but then a dark starburst erupts, when a director inside a director's film takes charge to breathe new life into an exit that seemed dead in the water. It's a man never letting go of pampering his love one last time, just as an artist will never stop blending nightmares and dreams into a swirling demi-monde. You can always count on auteurs to shine a shaft of salvaging light when the darkness is closing in all around.

UPN

UPNWORLD welcomes your comments.

0 COMMENTS

WRITE COMMENT