SANSHO THE BAILIFF

SANSHO DAYU ( SANSHO THE BAILIFF ) MOVIE REVIEW

RATING : 4 STARS OUT OF 5 ( EXCELLENT )

DIRECTOR : KENJI MIZOGUCHI

CAST : YOSHIAKI HANAYAGI, KYOKO KAGAWA , EITARO SHINDO

JAPANESE ( EXCELLENT ENGLISH SUBTITLES AVAILABLE ), 1954

For a lot of people, curiosity in cinema selection is so limited that a film made a mere ten years ago is considered ‘old ‘. For these new-born babies, a pic like Sansho Dayu holds nothing. But for others who have the gift of appreciating a filmic story irrespective of vintage, there awaits a somberly splendidly journey through human nature, loss and resilience. Hark ! I sense a few from the first sentence still lurking around trying to see what the fuss is all about. Let’s say three phrases ‘ black and white cinema ‘, ‘ Japanese film ‘, and ‘set in ‘ 1000 A.D ‘ . Cue massive scrambling and the hall is clear ! Now my friends, let us proceed.

Hollywood has nothing on Japan’s sprawling Jidaigeiki genre – period cinema, especially the enveloping black and white jewels. As redolent as the sweet ember-like aroma of woodsmoke, the best entries from this ilk have the power to whisk you away into another dimension of the universe, cloaked in muted hues yet with ravishing contrasts of colour, of houses and palaces sinewed and boned with more wood than you’ll see anywhere else and a haunting medieval miasma where the intrigues of human interplay reign supreme over any machinations of machine. Throw in action-‘n’-thrills and you get the whole Samurai shebang’s frissons rocking the screen. But what of exclusive pure drama in this ancient monochrome milieu ? – arguably the harder way to sustain audience interest, no offence meant to the rigours of good fight choreography.

Founding auteur and prolific director Kenji Mizoguchi assumes this challenge with sheer patience and non-sensationalism, narrating the story of a separated family where the ravages of time abscission the imagined glories of a united future. Ambitiously set in the late Heian period ( 794 – 1185 ), and painstakingly recreating the primordial milieus of that time, Mizoguchi employs his trademark elegant cinematography that handily props up every frame of this unlikely success.

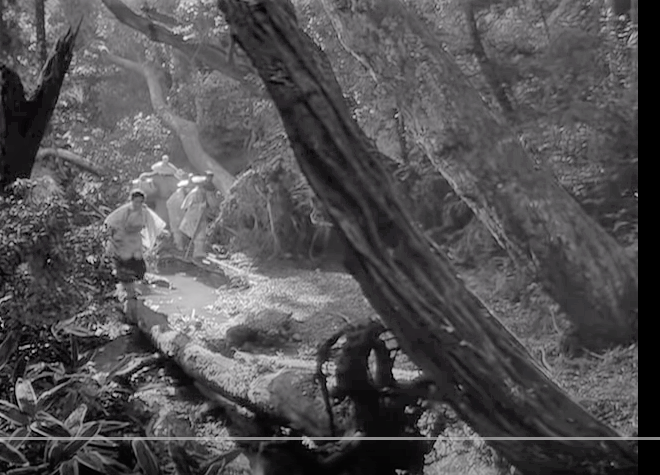

The two children who attempt to weather this odyssey are Anju ( the girl ) and Zushio (the boy). Their father – a noble governor, is rewarded for his good by being bundled off into exile. His family – the wife, girl and boy - are forced to leave their cushy perch and reach safe haven with only an ageing frail lady to accompany them. The hinterland they traverse has the same warm heart as that seen in ‘Onibaba’. The boat carries them alright but in different directions….

Pic may not blow one’s socks off on every level, but its focus on narration bulwarks the enterprise. This narrative purity is heightened by Mizoguchi’s collaboration with cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa who knew a thing or five about subtly dynamic camerawork, apart from solid framing.

Note the first scene of the movie, a shot content to rest on a magnificently forested frame where the large gnarled trees arc through foreground and background, with a log fallen over shallow water, a boy merrily hopping over this natural bridge while his family emerges from the back. Later as the exiled party moves towards a bleak future, they walk through a field aflutter with graceful cotton-like tufts of crop – a veritable painting. When the water-side separation occurs, the camera sits in the boat with the shocked mother looking towards the prow, as it is swiftly launched off the water and we see right in front of us as the children on the bank recede. The alarmed children run along the water bank towards the boat, the camera steadily keeping step just behind them. The next shot is right in front of the mother and it remains there while she floats away from us with the ether of the water progressively enlarging the gulf. What is so spectacular in all this boat stuff, you may ask ? Nothing actually, but with little touches of positioning in all the right places, the effect achieved is like all those little nuanced strokes that make one painting a cut above the rest.

Things kick up a notch with Mizoguchi’s famed knack for staging – for covering multiple elements of a scene or scenes with minimal cutting. Consider the sequence where the reigning thug is challenged in his own lair by a new authority – they heatedly speak at close quarters, then the rogue recedes into the background scoffing at the power of his opponent who’s had enough and orders the arrest of the stunned accused who shouts in defiance while the new nawab walks out the vestibule into the forecourt and more commotion breaks out inside but is swiftly suppressed by throngs of weapon-wielding soldiers cowing down the crook – all covered by the camera in a single superbly planned smooth take, panning a little to cover the distant action and then sweeping back when required, with the movement of the characters doing the rest. And there are, of course, certain unmistakably grand tracking shots, as in the one that moves along the wall of a spacious hall, a gliding linear ring-side view as the liberated throngs celebrate with drunken ecstatic fervour after decades of privation.

In behavioural nuance, some solid surprises await. We see Zushio ( the boy) and Anju ( the girl) torn from their privileged life and thrown into the walled servitude of a labour centre lorded over by Sansho – the richest and most heartless bailiff in this neck of the blasted woods. The boy was instructed by his father in the past, to always be kind to people; so we presume he will be grow up to be the beacon of hope in the middle of hell. But as both grow into young adults, Zushio suddenly sprouts shades of very selfish rascality while Anju glows as a maiden of nobility. She beseeches him to remember their father’s words while Zushio sulks and lobs at her a metaphoric splash of cold water. At that point, we see so clearly that Anju is the stronger of the two. That comparative arc progresses with the inimitable beauty of life as things plan out…

Little psychological tricks perk up the straightforward storytelling. Brother and sister are sent out for a macabre mission and they are breaking off branches when we remember a similar scene from their childhood. Zushio helps Anju break off a branch and then something snaps…. a smart and vital twig-break that kicks up the tale. Anju pleads with him to escape by himself, as chances of both of them running away would run a greater risk of capture. There is such an effective tension in that scene – we want both of them to escape but Anju seems to be sure of her rationale, and yet it would have been so nice if both brother and sister managed to get to safety. When a film has you rooting like this, it has done its job, pants dusted.

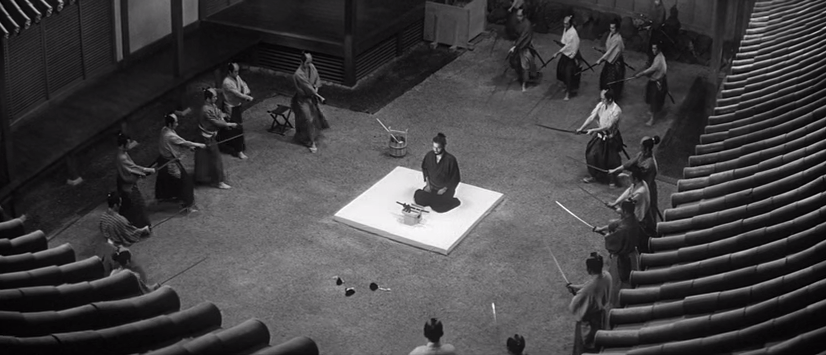

The greatest scene in the movie occurs when a survivor re-assumes a position of prominence and then bravely storms a den of suffering to liberate its tortured denizens. The scene inside the hall is remarkable enough in its multidirectional technical planning but then the outdoors crank up the unidirectional intensity. The camera looks on from a very supple crane shot and films the announcer as he descends stairs and ascends into the lives of those he addresses. “ Use of slaves has been prohibited “, “ From this moment on, you are no longer the property of Sansho The Bailiff “ and so forth rain the pronouncements, the chained folk cut free and given so many euphoric options in one minute where they hadn’t even been offered a single one in decades. With each electrifying decree, the crowd gasps in astonishment, and the liberator’s face is a wonderfully cracked mix of happiness, sadness, crying and inspiration. He can’t believe he is saying this - the voice getting hoarse with emotion - that this moment has arrived, that it has fructified, and that he will soon meet his blood whom he has been waiting so long to rejoin. All covered in one uncut genius shot – a marvel of staging. Some say that actually the scene at the end, by the elegiac seashore and trees, is the best one. Take your pick. I won’t grudge you – I’m not Sansho The Bailiff.

UPN

UPNWORLD welcomes your comments.

.jpg)

0 COMMENTS

WRITE COMMENT