Pather Panchali

Pather Panchali : Movie Review

5 stars out of 5 (Masterpiece)

Director : Satyajit Ray

Cinematographer : Subrata Mitra

Bengali (English subtitles available) , 1955

Sometimes, if you have to get to the heart of a legend, your scalpel will face a tougher time clearing the thickets of pre-existent praise surrounding it, than in the actual dissection of the subject at hand. A watching of Citizen Kane ,especially for a cineaste who is not yet deadened by the laureals heaped on it, may well require years of staying away from any comments on the movie, and active exorcising of any external opinions about it, before one settles down to the chimerical task of reviewing it without bias. Only a little less rigour is granted when one approaches the chance to analyze the joys and verities of Pather Panchali- the putatively canonical film that brought international acclaim to Satyajit Ray. Even without actively persuing his oeuvre, I have ended up watching close to a dozen works of this Bengali pezzonovante and consequently have no qualms in positing that Ray ranks as the pre-eminent auteur of early Indian cinema. So when the man who unknowingly initiated me into film analysis with his coruscating reviews, attests that Pather Panchali "kills" him every time time he watches it, that "no other film compares...at least in my eyes", I was re-stoked. But empathy did not instantly spring forth- I was a bigger admirer of the canvas and emotional span of this film's successor- Aparajito, and remember more vividly the intensely introspective, dare I use the world "existential", agony that suffuses Apur Sansar- the end of this trilogy and a film that prefigures other remarkable works like Wenders' "Paris, Texas". But a return to the heartland is never off the cards for a true native, hence I closed the curtains, ensured a suitably wide screen, and immersed myself into what is amongst the Government of Bengal's most valuable investments from the 1950s.

Statutory warning : This is not a compact review, it is a full-length reflection.

Throughout the course of this review, I'm going to throw around more theories than I usually do. After all, what is the fun in being a critic if you don't conjure up certain points that the director would never have dreamed of?

The canvas of Pather Panchali is primordial, an Eden that has ended even before it has begun.No government,council or panchayath is shown in the movie, the authority squarely falls upon the personal self and in this manner Ray succeeds in making this a private universe marooned in the sprawling outdoors.Cutting himself free from the clutter of Calcutta, or even a well-populated part of the provinces, he retreats into the hinterland and emerges with a fable that defies a moral.

The film commences with English credits, and then opens with a parchment on which Bengali alphabet is inked with sharp yet flowing flamboyance -a harbinger of the primary yet inspired storyline that lies in wait. World cinema viewers will note the similarity to early Japanese films in which opening credits show stylish alphabets inscribed on a stark screen. World-famous Sitar maestro Ravi Shankar kicks off the soundtrack in this intro sequence with a bracing tabla, then launches into jaunty sitar, and wraps up the sequence with a somber flute.

When I was trawling the web a year ago for the esteemed editorial page review that Shyam Lal lavished on Pather Panchali back in the days when Times of India was still a reputable newspaper, I never came across the full body of the article, but some choice gobbets from it had found their way into cyberpsace. Lal observed that there "is not a trace of the theatre in it" - a very germane consideration in the 1950s considering that Indian cinema was still finding its footing then and seeking to distinguish itself from the mores of theatre plays. Ray was also aware of the need for this distinction not only in 1955 but also years later in '66 when the only film of his that is named after me- an underwhelming movie,sadly -features its hero in a scene quietly complaining that a senior thespian is clueless about the need to not shout out his dialogues on the set's sound stage. In addition to featuring cinema verite acting, Pather Panchali steps far away from any artificial trappings of the theatre and sets itself in the heart of sylvan monochromes -one can feel the humid tropical stillness of the Indian heartland. Employing clear canvases, Ray is able to capture this Indian mofussil intimacy even when he changes into colour and brings his camera indoors into the bedroom of a wife in Ghare Bhaire. But in Song of the Little Road, the frames demand much more room- -the very first shot of the film shows a woman praying in front a tulsi plant, instead of an indoor idol. Successive shots show a bamboo grove filling the entire screen impressively while young Durga - a Mowgli without luck- filches a guava. She then hop-skips down a clearing and heads home.

Her parents live in poverty that is intensifying by the day.Hari's reports of landing a job in the very next month as an accountant and paid priest,and his plan to sell his original poems and plays to travelling artists, is all narrated to his wife Sarbojaya with such assurance that her face- despite all the years of failure and poverty- relaxes into a smile .She verbalizes her dreams of two good meals per day, of new clothes twice per year,and Hari adds to her visions by promising house repair and debt repayment within two years. Focus shifts to their children - referring to her infant son, Sarbojaya tells her husband "You'll teach the boy reading, writing and how to worship" and just at the moment when Durga (who is never sent to school ) sits on her father's lap, she says "We'll find a good match for Durga". Since gender equality is apparently in short supply, I hoped that she would at least get a good husband, or be resourceful enough to subsist inspite of a bad one.

Peripheral players are expertly sketched in - notice the skillful strokes with which Ray limnes an ephemeral character- a shopkeeper ( Tulsi Chakrabarti - a Ray favorite) who chats with a dubious visitor while constantly flicking his eyes towards his pupils and barking admonitions. Entertainment in the village, considering this is the twentieth century, is still primitive but the the children have no choice and eagerly seek it - a mythological play filled with grandiose and beseeching characters, a contraption that shows pictures of the city. I find it impossible to ignore the constantly detected theme here of societal safeguards suffering a breakdown - the inept father, the landowner unable to provide sustenance to those around him, a doctor's visit not having the intended long-term benefit, a motley group of characters who call themselves the "town elders" and who are neatly put in their place by an even-handed reply that tells them why their advice was not sought.

Aunt Indir -an elderly lady who is allowed occasionally to stay in the house- ranks as one of the memorably unique geriatric characters in cinema. Chunibala Devi blurs the line between reality and drama. Shorn of any artifice, we see only two teeth in her mouth: she is a nominally enhanced skeleton whom age has wizened, shrivelled and hunch-backed thoroughly.An apology for a saree drapes the remains of her body,the hair on her head is minimal and her eyes are half-closed - not one of us would bat an eyelid if she dropped dead the very next moment. One of the movie's emotional highpoints slides in early, when the old lady discovers a guava (a stealthy gift from Durga) in the fruit basket, and becomes open-mouthed and wide-eyed in sheer fascinated delight -one suspects Mahatma Gandhi himself couldn't have sported a a more sparkling visage if he had received the most rapturous news he could wish for .Anyway, we are surprised when we see strength suddenly coursing into her emaciated body - this happens when she energetically packs up her meager luggage in response to one of the strongest emotions seen in India down the ages - a mother-in-law's disapproval of her son's wife. Aunt Indir's personality is further coloured in with interesting character-deepening shades as the story progresses. One of Ray's directorial powers lies in the way he takes this potentially depressing character and transforms her (nay, looks more deeply at her even in passing) into a spunky octagenarian with no false notes.

Ravi Shankar's background music is judiciously deployed - there's a dysphoric drum-roll when a child is punished, a roiling ektara when Aunt Indir enters the house for a drink of water, an effervescent sitar when monsoon exposes the backsides of lotus leaves. He only stoops to a melodramatic underline when the film's biggest tragedy is lamented, otherwise his elemental music is a perfect complement to this pastoral saga.

While much of 1950s Indian black-'n'-white cinema focussed on story and melodrama while forgetting natural mise en scene, Pather Panchali is steeped in the redolence of Indian bucolia - Victuals drying atop a rock terrace, Brass vessel used for scooping up water, Rinsing the mouth and spitting out the water in the courtyard itself, Mother determined to feed rice into her child's mouth though the boy is disinterested and scampers around, Coconut grater with its crenellated blade protruding from the wooden platform on which the user sits, Tulsi plant sprouting atop a raised cuboid stone structure at the center of the courtyard....

It has been noted that some major works of British-era India did not feature the colonialists at all-- as if they didn't exist or as though their presence was too temporary or inconsequential in the grand scheme of things. Indirect evidence by way of train tracks aside, we don't really feel their absence here because the roles of oppression and neglect are ably assumed and upholded by the landowner's family. The landowner's wife is not bothered that Sarbojaya's family is starving, she only walks up to their house in an angry mood when some petty trash has been alleged to stolen by Durga. Her husband - the director has fun keeping his name as "Ray"- employs Hari without payment for three months, and is apparently so useless that he is never shown in this film.

Even a casual look at Ray's own life is enough to suggest why he was attracted to this work. In the movie, Hari is a writer who mentions that he comes from a family of writers and scholars. Ray's grandfather and father were writers and scholars, while Ray himself composed stories and essays. Further strong comparisons between Apu and Ray will create spoilers for those who haven't watched Aparajito,anyway it is not unreasonable to posit that Ray strongly identifies (not just in directorial capacity) with the eponymous journeyman of the Apu Trilogy and may even regard him as his figurative son. Ray was fond of children, he became a successful writer of children's literature, and the depiction of kids in Pather Panchali is a textbook example of the formidably difficult task of how to direct young ones in movies. Pather Pachali's children create no complaint, either in their acceptance of their fate, or in their acting chops. Young Uma Das Gupta embodies Durga -the girl who glides through this story while minding her own business for the most part, humouring her brother and helping others. A cryptic layer of complexity slides in when the pre-adolescent Durga looks at her rich friend whom she has helped to get decked in the finery of bridal wear - the look on former's face carries full import only when one looks back at it after the movie's end. Apu, not just in this movie but also in the next instalment, is a boy who is good-natured to a fault - but what the heck, you need someone like lovely little Subir Banerjee to eventually balance out the brats in cinema. We see the famous close-up shot of his visage as it witnesses a punishment -his face recoils with terror once,the lens takes in his raven black locks of hair, wide open eyes glistening with fear, the tender flesh of his nascent face contrasted against the hard edges and rough texture of a pillar beside. At a much later stage, when he reaches home after school and hears the cries of sorrow from inside the house, the camera creates a magnificently poignant shot by slowly zooming in on this little figure who has stopped in his tracks,his face quietly registering the pathos, chest swathed in a dark cloth, with an umbrella's handle jutting out from his figure like the prow of a ship- very early in life,the waves of trama and responsibility heave upon him.

In a film full of amateur actors who are marvellous in conveying spontaneity and polish, Karuna Banerjee stands out as a prime example of effortless thespian finesse. Her Sarbojaya is a woebegone Indian caryatid bearing the weight of her collapsing household. Her smiles are landmarks in the movie. When she is not involved in assiduous domestic work, Sarbojaya is burdened by a countenance of brooding melancholia with which she gazes at the fathoms of her predicament. This is combined with an alacritous sharpness of mind that marks her out as a true lady of the house. She shrewishly snaps at Aunt Indir for taking up undeserving space, senses in a flash that Apu is asking for money when he runs up to his Dad ("don't give him money!' she warns from outside the screen), defends her daughter against a taunting witch, runs in to rescue her son from a manhandling, and tries valiantly to prevent the house from falling to pieces when her husband is away. Apart from being a model of supportive feminity, she is more of a man than her husband.

Apropos the man of the house - Hari (portrayed perfectly by Kanu Bannerjee)- I am convinced that Ray has a larger narrative in mind here. I feel he believes that men like Hari are no longer viable in India, that the country will die if men like him persist. Species like his, are seen as dinosaurs .Hari is a not a bad man, but we suspect he is pusillanimous, and a casualty towards the family that he is supposed to protect. Early in this story,he has lost his economically useful orchard thanks to the same old family wranglings and vendettas ,and it's likely that he was the timid one in the fight. Ostensibly lacking condoms or other contraceptive devices to prevent a swelling brood, he doesn't realize that his plans for new means of earning a living, are too unreliable to supply the badly needed finances. He is mature yet not aggresive enough. Early on,his wife reminds him of the ineptitude of his plans,but that still doesn't rouse him adequately. Yes he does take corrective action eventually when things fail to look up, but when he repeats "God does everything for the best", he over-stretches theological precepts and does not realize that we are duty-bound to exercise the God within ourselves. In "Ashani Sanket", a dubious medical practitioner falls flat in a drought, in "Nayak" a filmstar is beset by doubts centering on real achievement in life, in "Aranyer Din Ratri" none of the three men impress, "Jalsaghar" features a disintegrating Zamindar, "Seemabaddha" shows a corporate man who seems to be "ascending the stairs" and yet the end shows him racked by capitalistic doubts, "Ghare Bhaire" has an altruistic aristocrat who nevertheless tumbles into a sub-optimal end, and ultimate fecklessness is toplined in the hilarious "Shatranj Ke Khilari" where the Nawabs fritter away their lives while the Brits earnestly carry on their rampage. One gets a continual feeling that the men in Ray's films struggle to be real men - there are exceptions of course but they are few.

Subrata Mitra constructs the visual world here with the sure eye of a top artist. Colour would have destroyed this black-'n'-white chiaroscuro. High-resolution images would again have hardly flattered the man-made shambles which are enclosed here by the aesthetic-transcending woods. His first remarkable shot rolls in when he takes a close-up of little tomboyish Durga -fragile yet independent- crouching in the woods while stumps of bamboo give further gestalt to that composition. When the kids tail the candy-man in the hope of gratis sweets, the camera's gaze tilts onto a lake to record the mirror-image of that dreamy pursuit. When a chided daughter is grabbed by her tresses and dragged out by the mother ,he employs short-range shots to show the angry immediacy of the moment, but when the mother has despatched her out of the crumbling doors, and both are parties are collapsed in the trauma of the incident, he pulls back the frame to show a huge crater in the courtyard wall- the girl can easily step back in if she wanted to. Later when the little brother follows his elder sister in an attempt to re-establish camaraderie (after all, she is his only sure companion in these boondocks) the film floats without a care in the world, in the vast acreage of the fields. Trees give way to electrical utility poles sprouting porcelain insulators, and the train tracks loom. I half-expected Durga to ambush her kid brother as he wanders through this stillness, the screen graced by white arcing feathers of sugarcane flowers, but he is instead gently hit by a sugarcane stump - a gift from his sister sitting nearby.This is where the film establishes its strongest affinity with early Japanese cinema in monochrome- there's an abolutely unhurried tranquility to the scene, a sense of contemplation where there is ample breathing space - man and nature alone - as if you yourself are in that field.The film-maker here is not calibrating his work with the ring of the box-office register nearing 1000 crores, he'd doing what he feels to be his art and craft.

Cultivated consummately on the fertile material of Bibutibhushan Bandopadhyay's 1929 novel of the same name, Pather Panchali had a tepid reception in Calcutta for its home-country premiere but others made sure that Ray was not let down. Cannes spotlights popped, notorious queen of film reviewing - Pauline Kael- was impressed, mercurial critic of NYT Bosley Crowther conceded it engaged him while across continents, it riveted Akira Kurosawa. I was not too curious to find out Roger Ebert's liking for this movie because I sensed what his verdict would be.

So Pather Panchali's structure ripples with shifting shades of stoicism, and perhaps it is only a unsaid footnote that this way of life is no longer sustainable in an India of which Shashi Tharoor said "contrary to popular belief ,India is not an under-developed nation, rather it is a highly developed country in an advanced state of decay". Equally,I will never be able to refute the proposed counter-point that Ray accepts this state of affairs without complaint - it is a world falling to pieces but it is his duty to record rather than ameliorate -and in this, he is not far off from the wild-life documentarians who do not intervene even if the cub is dying while its mother is away. To better understand what Ray wanted to convey in entirety one has to peruse the rest of the series, nevertheless Pather Panchali undeniably stands by itself as a complete story. Its purports are flung open for eternal interpretation, yet the movie roots itself as a sure portrait of mono no aware .One man sees the ship sinking, another sees it battling the waves, while the complete director in Ray reserves an inclusive vision that challenges judgement.

UPN

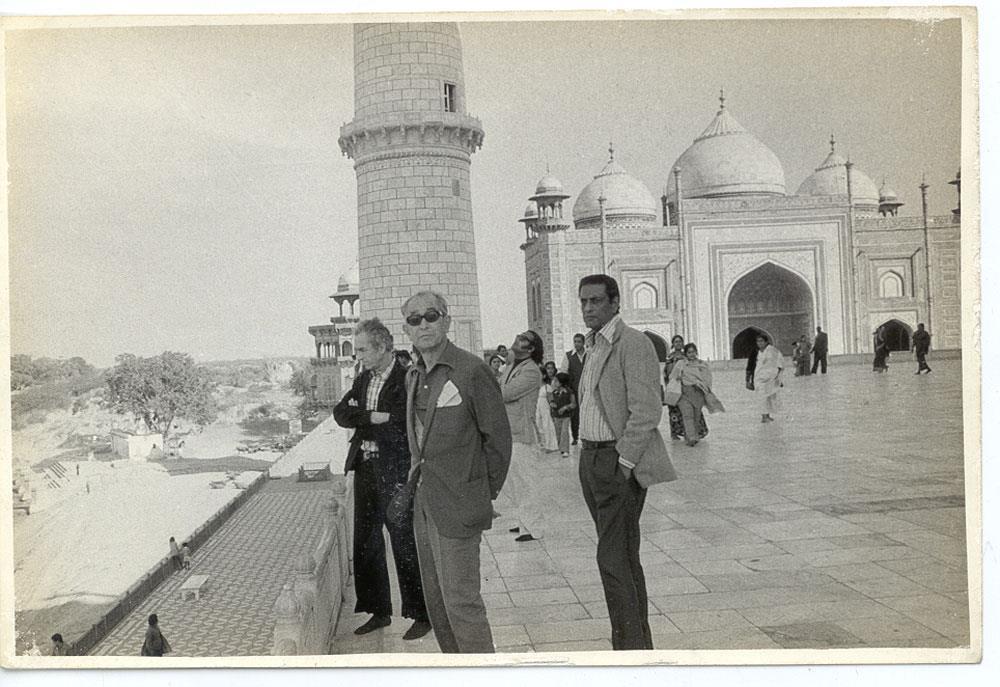

Satyajit Ray (right), Akira Kurosawa (centre), Michelangelo Antonioni (left) at the Taj Mahal

UPNWORLD welcomes your comments.

0 COMMENTS

WRITE COMMENT