ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT

ALL WE IMAGINE AS LIGHT : MOVIE REVIEW

4 STARS / 5 (EXCELLENT)

DIRECTOR-WRITER : PAYAL KAPADIA

MALAYALAM, MARATHI, ENGLISH (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE)

2024

INTIMATE LANGUOROUS PORTRAIT

OF MALAYALI NURSES

AND DIVERSE LIFE ARCS

NOTE : Plot details are discussed in detail in the review. Those who want to avoid spoilers may return after seeing the movie.

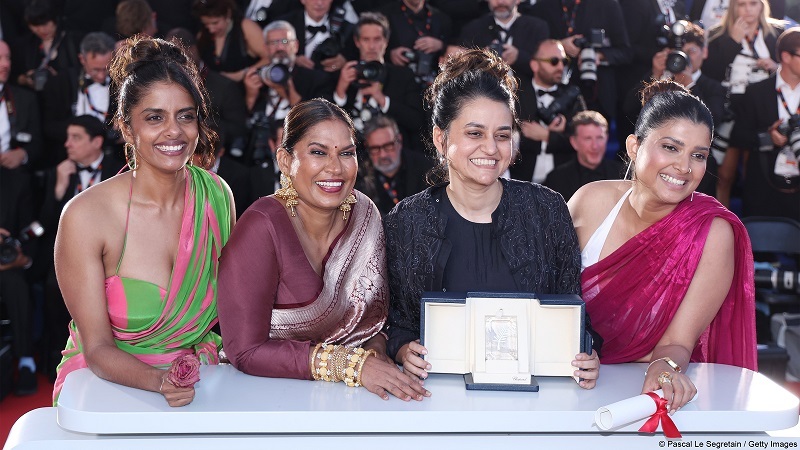

I was getting ready to pillory Cannes for their decades-long shameful neglect of Indian cinema on hearing the news that director-writer Payal Kapadia's "All We Imagine As Light" had won the 2024 Grand Prix (the festival's second prize). But after watching this excellent film, I am slightly mollified (I was mallufied ages ago). Pic is an intimate, languidly observed portrait of two Malayali nurses in the central Indian state of Maharashtra, and their differing arcs - not only as a study in personal contrast but also as a synecdoche for the conservative-radical diversity that animates modern India. This is a full-blooded art film - not as radical as as something like 'Zerkalo' but audiences who cannot tolerate slow pacing and prefer mainstream cinema will go crazy in the wrong way here. Cannes has often favoured films that adeptly slice open the social milieu for display and this one takes the reflective mango in this regard. As a bonus for certain focus groups, Kapadia kindly throws film analysts liberal bones with frequent use of visual motifs to reflect what is implicit in the title. As for whether Cannes still deserves damnation for their chronic disregard of Indian films for the top prize - yes, absolutely - they missed the steamer on Shaji N. Karun's 'Vanaprastham' (1999), Anurag Kashyap's 'Ugly' (2013) and 'Gangs of Wasseypur' (2012) and have proved themselves clueless when it comes to acknowledging one of the world's great film cultures.

The story braid involves three coursing strands - two are nurses in a Mumbai hospital, while it is unclear whether the third one is a nurse or an attendant. Their ages inscribe a gradient. The youngest is Anu (Divya Prabha in a wonderfully winsome performance) a youngster in her twenties with a carefree spirit that defines adventurers in that halcyon period. Prabha (Kanu Kusruti) is a experienced nurse in her thirties who calmly conducts her demi-monde, the anchor who allows the movie to explore its societal contrasts and the interplay between the quietly accepted but inexorable reality of much of the story and the oneiric waves that finish it. Prabha and Anu are room-mates, both from the same home state of Kerala, and they get along well with each other - Anu looking up to her as a senior. Parvathy (Chhaya Kadam) is in late middle age, spunky in her independence but her continuity in Mumbai is threatened by her precarious housing situation - a domicile dilemma that plagues hundreds of thousands in the city.

Anu has started her nursing career, but more exciting things seem to be happening to her outside the hospital. The other nurses gossip that she, a Hindu girl, is going out with a Muslim boy, and indeed she is, advancing keenly in her relationship with him, even as her household members back in Kerala send her pictures of potential bridegrooms, expecting her to have an arranged marriage. Arranged marriage has turned into custard, a failed apfelkuchen for Prabha, with her lightning quick 'wham-bam thank you ma'am' arranged alliance with a bloke with whom she could barely speak a few words before he pushed off to Germany where he's been for years and God knows what pies he's baking there. Prabha patiently waits for this ghost, her personal life cryo-preserved in the heat of Mumbai, immersing herself in her nursing work. Parvathy meanwhile is being pushed out of her modest lodging where she was never a legal occupant, and rather than live with her son's family in another cramped quarter, she decides with her self-esteem that she is better off moving to the countryside and eking out a living there.

What consistently distinguishes the film is its calmness and stillness - this is for serious cineastes, while restless punters will peel away. Kapadia does not need the bonus of background music, whereas so many other film-makers would insist on liberal doses of this both for brass-tacks narration and hooking audience interest. Kapadia isn't exactly directing Fred Zinneman's "Day Of The Jackal" - a thriller which jettisoned background music despite the narrative demands - but even in these admittedly calmer waters, she is able to sail her catamaran with only the gently susurrating sounds of waves, by focusing keenly on her character's inner lives and caring two hoots for narrative momentum.

Her ability to create memorable scenes comes through. In the first ten minutes, she is able to capture a vital slice of day-to-day Mumbai simply by targeted recording. There are the incredible masses of people in the city's railway stations and trains. Mumbai trains have ladies-only compartments and the lens here observes ladies from various walks of life. The camera trains itself on Prabha holding on to a rail in a rail and calmly gazing about - cinema lavishes its frames on glamorous stars - here is a film that gives marquee framing to the lady you see yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Then there is a wonderfully languid scene showing the winsome, youthful Anu as she slouches and speaks with a young patient across the consultation counter. In the afternoon, the queue dies out and Anu, alone in the consultation booth, shoots the breeze, twirling around in her chair as Emahoy Tsegue-Mariam Guebrou's whimsical pearl-swirls of piano perfectly accentuate the charmed feel of the moment.

Later, on a rare occasion of friction between the two colleague-room-mates, the elder Prabha apologizes to Anu for admonishing her. Anu is changing her clothes and I wondered whether there was a real need for upper frontal nudity in this scene. But then it becomes clearer - Anu's silent reply implies she's unafraid to show uninhibited acts not just now but elsewhere too, while Prabha looks away, probably understanding why Anu acts the way she does.

In a nocturnal scene in a park, Prabha and a doctor who is romantically interested in her, sit on swings a little distance apart, speaking in Malayalam. The doctor has had enough of Mumbai but he hints he may stay behind if Prabha reciprocates his interest. "Married aana, doctrae", Prabha softly replies ("I am married, doctor"). In their line of work, they often have to speak in English, but here, Prabha probably switches to English to introduce a slightly formal, removed note to her polite rejection.

Sometimes, the tone is set without human figures. Prabha speaks to Anu at bed-time about her absent marriage, but the initial scene stays on a blue sari gently swaying in the wind against a black night - a simple, beautifully coloured frame by itself, aside from being an apt metaphor for what is being said.

But some scenes are not so innocent. In the countryside, Prabha squats in a clearing in the woods to relieve herself. Since Kapadia and Kusruti have taken the trouble to show this scene, I'm sure the former has an open explanation for why she deposited this shot here. Many Indian viewers though would have their hackles raised by this depiction, alleging that Cannes and other Western institutions tend to celebrate Indian films that show disreputable practices like local characters doing open defecation.

*

Payal Kapadia's picture is one of the very few that frontlines and gently celebrates the lives of nurses from Kerala, the geographically compact state at India's southern tip, known for its multifarious rich culture, its language being Malayalam - a palindrome, and an exquisite tongue-twister of a language with beautiful Sanskritic undertones. Kerala nurses over the decades have acquired a kind of primacy of brand, like French chefs and Italian violin makers. They are paid criminally less in Kerala and the rest of India, which they try to counter by moving to metros and all over the world from America to Africa to New Zealand. Anu is still young, and her nascent hospital duties are still in their early stages. But Prabha, especially, with her experienced practice, embodies what is great about many Kerala nurses, with their calm disposition and relentless work ethic that keeps the world's engines whirring.

Pic is beautifully illuminative of current-day india's ancient-modern divide apropos the mode of marriage. India is one of the world's epicentres of arranged marriage - it works for some while it stands to reason that countless lives have been destroyed thanks to the profoundly foolhardy practice of hitching together two people who have little to gel with. Prabha is a prime example of this atrocity, and she does a fine job of soldiering ahead with her martyrdom, courtesy her conservative nature (we cannot comment on her unseen upbringing). Anu meanwhile is on the other thematic coast, busy romancing a Muslim youngster (Kapadia de-ecalates the complexity level by opting not to go for a Muslim lesbian as the partner, otherwise she might have won a Palme D'Or). The Hindu-Muslim equation in India is one of the world's great flashpoints, far pre-dating relatively recent catastrophes like the Israel-Palestine conflict, and it is this ancient monster Anu tries to needle and tame, by opting to romance a Muslim man. She is serious about taking it to the next level, wearing a burqa and travelling to his place which is meant to be briefly empty of other people so that both of them can presumably have an ice-cream together in private solitude. Do I have a problem with these two people from vastly different religions and cultures being together ? No, but try telling that to the local society in general. What kind of problems will they encounter and how will they surmount it if they last ? See Mani Ratnam's "Bombay" to see if a comparison can be made. Perhaps Kapadia can explore this in Part 2 of AWIAL, if she can persuade the producer (Avial, by the way, is a lovely Kerala vegetarian delicacy).

We have discussed individual marquee characters but the film starts with unseen characters describing their experience of Mumbai. Like the ground flight to any great city of the world, the voices tell us how one left home at a young age after a fight with family and arrived here, and the unpleasant living conditions. Mid-way through the movie, pic circles back to these unseen voices one of which observes you are free to do anything in Mumbai except for complaining or feeling dejected even when you are in the depths of misery. At this point, an interesting turn happens. Without any hint or intimation, we see all three ladies travelling to the sea-side country-side. We know Parvathy was forced to move, but it is unclear what is going on with Prabha and Anu.

There is a lovely aerial shot where the lens moves from the bus moving down a curving lonely road, past laterite soil embankments to the vast gleaming sea. This is the Konkan coast, with an abundance of beauty, nature, solitude, seafood et more. The three ladies settle down in a shack. Soon music and booze flow, and Parvathy and Anu surprise us with their nice dance moves. Prabha does not partake of either sauce or prancing but from one side of the room, she watches in wonder at her two companions unwinding. The countryside brought out something in these Mumbaikars that Mumbai could not inspire.

Here in the countryside where the constriction is less and the exhalation is more, each lady can breathe a little easier. Parvathy can chillax a bit, her housing no longer threatened. Anu and her lover can meet and do whatever they want, away from prying eyes. As for Prabha, she gets a special occult gift from her godmother Kapadia. Life, often, is what happens to you when others' plans supercede yours. In films however, plans can get a little more daring and actualized, as long as the producer and box-office are not breathing down your neck.

Prabha takes the chance to go to a drowning rescue and scores a triumph thanks to her professional training. The victim - a man - miraculously awakens and the crowd claps (Indians are generally appreciative but they don't often clap like how Americans do - witness the recent bystander video where an Indian man was the one and only, completely miraculous, fully cinematic survivor of the notorious Air India 2025 plane crash and nobody clapped as this lone injured survivor walked away).This rescued man and Prabha are then alone in a room at night with a single suspended light-bulb (that light-bulb is again borrowed from the title), she nursing him as he lies down tired but recuperating. He then speaks up as her long-lost husband, and Prabha accepts this, knowing that in the vast unknowable ocean, Stellet Licht, and in certain types of stories, anything can happen. This sustained oneiric scene, with silences tenderness smiles tears, subtly changes the fibre of the film, teasing the nature of its revelations, valuing reflection more than reality. She has waited so long, for years... until this night in a dark room with a celestial controlled glow, when her husband comes back to her and tenderly expresses his affection. The magic realism comes as a balm to her, this lady who has spent a lifetime administering salves to others.

The film has a carefully applied visual scheme. In the city, night is mostly chosen, the better to show millions of lights from apartments, the moving light from within illuminated trains traversing the dark, referencing the film's title. Night or day, the camera's exposure levels are dialled down in the city, creating a soft starkness - an aesthetic of its own, like kohl-lined eyes. In the countryside, the lens' exposure levels are cranked up, over-saturating the frames with light.

Pic's sparely used background music, which sounds like standard synthesizer stuff, is really only that. Of much more charm and what's that ?! recall value are the borrowed piano riffs composed by Emahoy Tsegue-Mariam Guebrou.

Kapadia's triumph in extracting thespian finesse lies in the way each of the three female personas seem to have been plucked straight out of real life with very little buffing up.

Kanu Kusruti's visage is channeled into a subtly melancholic, tranquil physiognomy, which is the face of this film's noble strength. Prabha's persona is the archetype of the dignified Indian lady who goes through life doing her work, while leaving the crusades and brouhahas to her more feisty sisters. Kusruti employs a relentlessly calm demeanor to reflect the inner gentle steel. This is essentially a gentle soul and even when she is spurred to the rare eddy of aggravation, Kusruti makes the waves soon subside into the calm sea inside Prabha.

The story arc's carefree, daring angle is consummately conveyed by Divya Parbha's winsome turn. Her pretty face, comely cheeks and child-like innocence modulate smoothly to convey a variety of moods - a touch of annoyance with a click of tongue, upturned cheeks and slight creased eyes, then the same eyes widening while she semi-whispers and pantomimes to conspiratorially clarify the query about a remunerative sterilization procedure.

Of the films that I have watched, I could see the merits in four Asian films that won the Palme D'Or - Ballad of Narayama (1983), Unagi (1997), Taste of Cherry (1997), Shoplifters (2018) although Jacques Audiard's Asian-inflected "Dheepan" (2015) did not impress. 2021 Grand Prix winner "A Hero" by Asghar Farhadi, was a beaut. "All We Imagine As Light" struck me as merely decent on the first viewing but a second one brought its amorphous qualities into sharper relief. This is a multi-layered social document and Kapadia deserves the accolades she's garnered.

UPN

UPNWORLD welcomes your comments.

0 COMMENTS

WRITE COMMENT