Harakiri

Harakiri

4 & 1/2 stars out of 5 (Outstanding)

Director : Masaki Kobayashi

Japanese (splendid English subtitles available), 1962

"Who can know the depths of another man's heart?"

- asked by Hanshuro Tsugumo

Apart from its sheer story-telling gravitas and technical splendour, Kobayashi's Hara-kiri is especially lauded for its plea to look closer, to examine a little more deeply the troubles of those not as fortunate as us. When I watched it for the first time, I was blown away by the arresting wallop of this tension-saturated story's narration , and it was on the second viewing years later that I registered with more delicate acuity, its eloquent entreaty for a more compassionate look at the surface issues of our brethren. As we rise higher in the material world and assume bigger office , it becomes that much more easier to adopt a somewhat dismissive, supercilously severe attitude to those in the "lower" ranks. They make mistakes and sometimes we lose no time in damning them for it , on occasion with brutal punishment without expending energy into finding why they are behaving that way. While almost everyone is prone to this lapse, those have never climbed the hard way are particularly susceptible. Particularly in Japan, the practice of bowing to the larger system and the concept of "honour" being maintained at all costs, looms especially large but of what use is honour if it makes us lose everything dear to us? Hara-kiri takes on the form of a formidable Samurai drama and builds this visceral sentiment with inexorable power, the vise of its narrative swirling and tightening until the physical carnage at the end isn't necessary - the foes have already been annihilated with gentle words. World-class cinematography and flawlessly strong acting further power this monochrome scorcher.

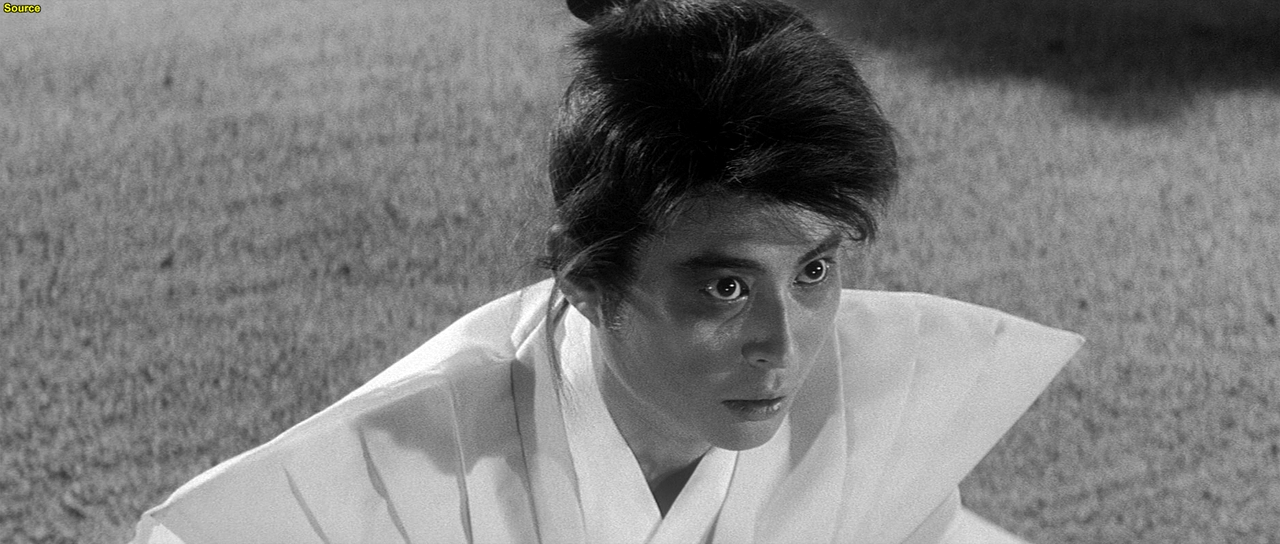

Pic opens with a wide-angle black-'n'-white canvas, the neatness and sparse beauty of which is the trademark of director Masaki Kobayashi. Notice how clean these compositions are, whether it is the large ground ouside a chieftan's house, the inner courtyard with its settled pebbles and carefully coiffed platforms for sitting, or even a poor man's wooden house bereft of much conveniences and yet almost spacious in its tidy gestalt. The framing is immaculate when Motome Chijiwa (Akira Ishihama) - a young Samurai struggling for survival - sits with folded knee - in a martial lord's house in front of a tough-jawed warrior who listens to his case. It is 1630 in the Edo region of Japan - peace has been declared in the land but it has devolved into internal war for the highly trained swordsmen called Samurai. They find no employment now, jobs are scarce with workers pouring into any open job-site and Motome is pushed away by a supervisor who cries out that the supervisor will be punished if authorities find out that the formal warrior class is being employed for menial jobs.

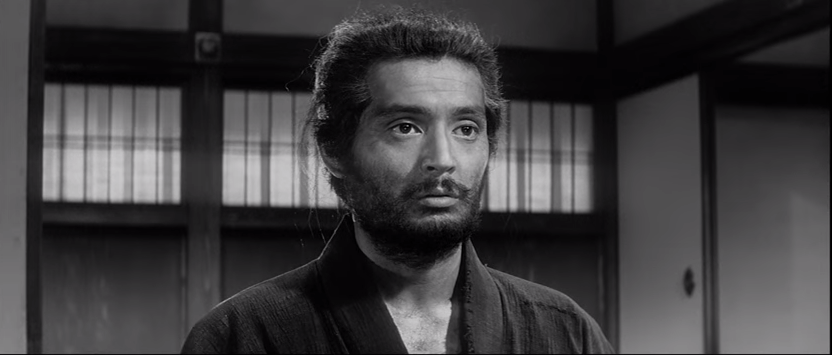

Motome reports to the House of Lyi , as other Samurai have done before him, that this utter penury is so dishonourable that he would rather commit Seppuku by disemboweling himself with his own sword in this martial house's courtyard as a final act of honour. The House of Lyi, manned by fierce-looking superiors, is fed up with this pattern of supposedly suicidal Samurais. They see that many such applicants are willing to accept some money and go away without killing themseles as they initially declared to do. At this stage, Kobayashi racks up the sense of foreboding , panic and icy fear with such elan that the ensuing twenty minutes ranks as one of the most implacable turn of events in black-'n'-white cinema. A few days later, a middle-aged man named Hanshuro Tsugomo (Tatsuya Nakadai), bearded and rather emaciated-looking, shows up at the House of Li with a similar request. He is told the story of Motome Chijiwa as a warning - but Tsugumo, with a wry expression that is beyond gallows humour, calmly states that he will indubitably execute as promised.

As great as the previous tightly coiled sequence was, this succeding chapter matches it with its slow burn and unbearable tension which Tsugumo stretches far past breaking point with a story he unspools. Counsellor Saito (Rentaro Mikuni) , heading the house in the absence of the martial lord, is , to put it precisely - driven nuts - by this seemingly interminable narration by the grave-faced Tsugumo. But I never got tired of hearing it as the latter lays one dialogue upon another like one revelatory card against the next one till the stakes indicate not just one death but many more. Saito, his strings plucked like a hen stripped to the bone, retreats to the house unable to take more.

In other jidaigeki (period-films) like Kurosawa's great "Throne of Blood", the performances though solid do not evoke my specific praise but in Harakiri ,the thespian finesse is on prime display - this could very well have been a starkly lit theater-drama. One can almost feel the cool breeze of happiness coursing through Motome's smiling, immensely relieved face after the stifling humidity of despair. Alas later, stomach-churning panic sets in to seize his mien. Tsugumo's nominally amused, mostly dead-serious physiognomy never ever raises its voice but the prosody of his message undulates with the timeless meaning of great scripture. And then there's Saito, more cunt than counsellor, who's so drunk with power and delusions of tough wisdom that his sobriety is nullified by incurable hauteur.

I was vastly disappointed by the fight at the end on my first viewing - having brought me to the very peak of expectation, Harakiri's climactic sword-fight seemed not even close to the supremely choreographed ahead-of-its-time bristling magnificence of "Daibosatsu-toge"s finisher. But then as Saito himself says, Tsugumo is a "half-starved" Samurai who's already been through many hells so it is perhaps unfair to expect him to again fight like Japan's greatest champion. The denouement is a sobering indictment of the way history often operates, and the film eventually reclaims its spell-binding emotional and technical territory. To watch Hara-kiri, then, is to acknowledge that even in 1962 when so much of the rest of the world was learning the ropes of top-tier movies, Japan was already capable of engineering peerless cinema.

UPN

UPNWORLD welcomes your comments.

.jpg)

0 COMMENTS

WRITE COMMENT