I Am Love

Io Sono L'Amore ( I Am Love) : Movie Review

5 stars out of 5 (Masterpiece)

Director : Luca Guadagnino

Italian (English subtitles available) , 2009

WARNING : It is not possible to elucidate the finer points of this special picture without elaborating on some specific plot points. I have left out some other spoilers which did not necessitate mention, but if you'd rather see the movie with no knowledge whatsoever of its turns, please skip the review for now while coming into receipt of the tip-off that this is that rare feature film that blends the operatic with the everyday in a deeply stylish, viscerally emotional way.

Review Begins :

Few countries make, nay, have the style statement that Italy embodies. A tourism paradise with scores of stunning locales inland and by the sea, magnificent old-world architecture, haute couture, luscious cuisine, luxury furniture and more... In cinema, more than the better-known Italian cine-landmarks , I remember 'Il Conformista', not so much for the emotion as for the gorgeous soft-palette colours and graceful camera flow that gently suffuses the entire picture. In the twenty-first century I remain very glad to have been introduced to, and covet as a treasure, my copy of 'lo Sono L'amore' (I Am Love) - a film by Luca Guadagnino that unites almost all the afore-mentioned elite elements into an impossibly beautiful masterpiece.

It focuses on a very wealthy family in Milan that has woven its riches from the textile industry. There is emotional turbulence in the very first sequence - a lost horse race which the family always previously won, and a surprise decision in a declaration of power transfer from one generation to another. The subversive influences, in an impressive array of forms, never stop from there onwards, taking apart the family in multiple ways.

This exact same story could have been told by a lesser director in a fairly pedestrian way, but the helmer here uses the high-end setting as a launching board, to wed everyday behaviour and feeling with an agile tendency to naturally sculpt and let soar scenes of hypnotic intensity and operatic grandeur. Guadagnino directs with such beauty and controlled flamboyance that even if I were charged not the usual $20 that is the price of a movie ticket but $400 that is the tariff for a high-profile opera (that 'I Am Love' effortlessly often simulates) I'd have left satiated at the end of the performance.

The imaginative and grandly conceived opening, gazes at snow-swathed Milan which then flows into a memorable mansion of modern-meets-classic design.

Emma (Tilda Swinton) is the mistress of the house and we are introduced to her as she busily attends to the details of a large family dinner planned for later that day. Set to be held in a stately, beautiful high-ceilinged dining room, it will herald an important announcement by the patriarch who lives in a different house. Her youth was spent in a modest household in Russia from where she was whisked away by wealthy heir Tancredi (Pippo Delbono - subtly effective as a stuffy middle-aged man of privilege).

This couple, we sense in glimpses, now live a life shorn of the kind of sentiment that somehow makes heaven-selected pairs lead their entire mutual lives in passable commitment. They don't fight , but nor do we sense a bright flame still burning.

They have three children; the eldest appears to be in his mid to late twenties - a slender, handsome blue-eyed young man named Edoardo (Flavio Parenti in a delicately handsome performace). With a heart that is good and large, he cares for his friends, willing to go the extra mile for them while planning keenly to ensure that his factory staff have secure long-term employment. No wonder his grandfather, who made their estate what it is , likes him more than he does Tancredi.

The churn occurs when Edoardo befriends Antonio (Edoardo Gabriellini) - another young colt who had defeated him in the horse race. Antonio appears to have elements of North African or Middle Eastern extraction; he's an up-'n'-coming nouvelle cuisine chef whose creations wow everyone who tastes them. There's the saying - 'When your friend goes the extra mile for you and arranges the finances and logistics to inaugurate your professional dream, please do not court his mother'. Antonio evidently has not heard, neither does his care, for this counsel.

When deciding to make a film, the first choices I would make is to appoint a high-quality cinematographer and music composer - in particular, men or women who understand aesthetics and restraint, and when to cut loose. Luca Guadagnino aces the score on these two invaluable fronts. He selects and inserts John Adams' orchestral compositions which were already cemented much before the film's idea was conceived, and five-star lensmanship by Yorick Le Saux.

Their dual magic, further elevated by the director's visionary wand, manifests in various showpiece sequences.

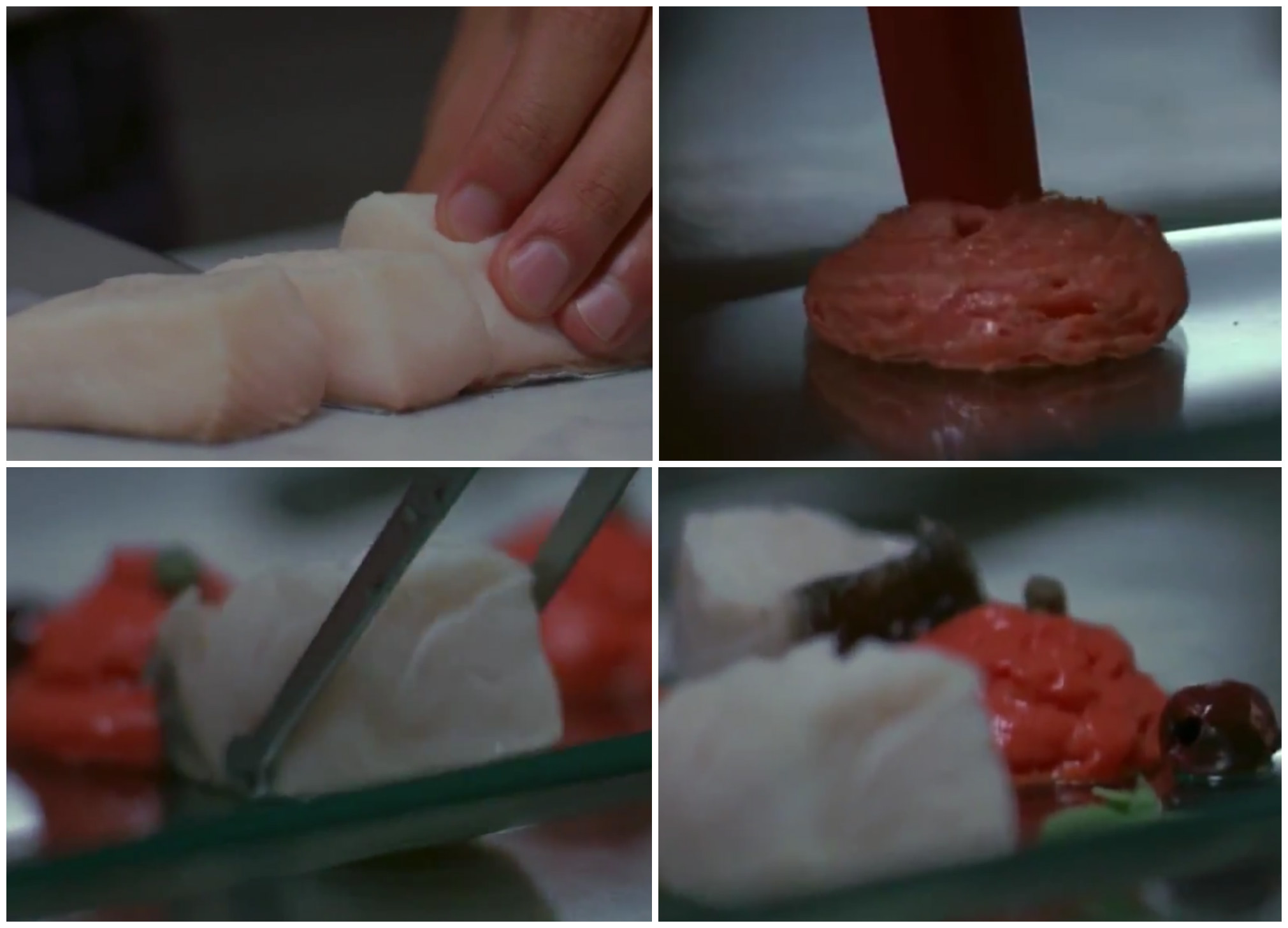

When Emma, her glamorous, augustly catty mother-in-law Allegra and Edoardo's fiancee lunch in Antonio's restaurant, he sends out the best of his modernist cuisine flourishes for them. The way he synthesizes a gorgeous deconstructionist version of the 'Leghorn-stye Cod' is a joy to watch in itself. On tasting it, Emma gets the first frisson on what's to come. There's even a sneaky meaning in the main course for the senior lady (an egg yolk and pea cream dish that a man would probably scoff in one bite), a relatively mainstream "mixed fish and crunchy vegetable" for the fleshily smooth fiancee.

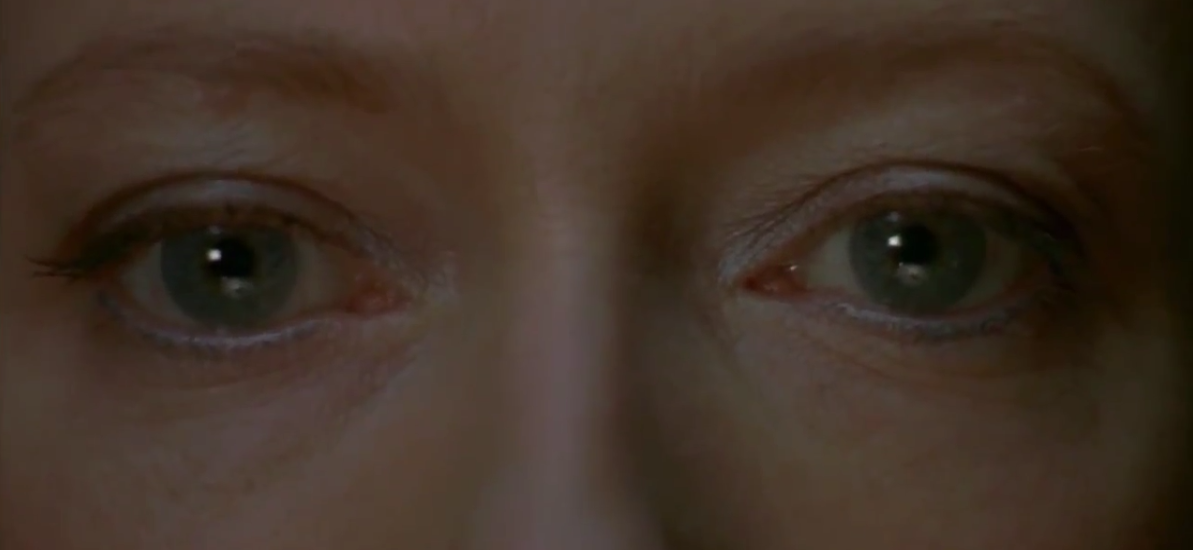

To Emma however, his presentation elides quantity (of which Emma has had no dearth of in her millionaire household) and focuses on profound pleasurable quality (which she may not have had enough of). Shrimp, of those intensely hued small Mediterranean ilk, and ratatouille (stewed vegetables) are placed in front of Emma. Her fingers holding the fork and knife attend to the task with gentle incredulous pleasure and on tasting the shrimp, her eyes close and her face and eyes slowly writhe... as though she's being caressed both inside and outside. The scene's natural pace slows down to join her in languorous ecstasy. Lights dim off elsewhere and create a soft spotlight around her whilst music carefully enhances intimacy and expansiveness in the background. Brad Bird would have approved. The scene is a key example of how cuisine (with a subtle consistent focus on seafood) is used throughout the movie as a device of subversion. After such a seduction, one wonders what the impossibly sated Emma can possibly do to fend off the flirtation...

Emma's mystic searching in refulgently sunny San Remo - a little easier than finding a needle in a haystack - is recorded with panache and suspense. With palpitating senses, when the target is close by, she wonders how to make contact. Her reaction in an earlier notable sequence, where another parent might have suffered apoplexy, on discovering that her daughter Elisabetta is lesbian, is extraordinarily accepting and calm as the lens tracks her movement through the city and amidst Duomo di Milano's formidable geometric mesh.

And then there's the opening sequence itself. Choice captures of wintry Milan then segue into that gorgeous mansion which makes stunning use of marble, glossy wood, upholstery and royally large windows which, especially in the lounge, stretch from wainscoting to ceiling, offering fairytale vistas of filtered light coming in from the garden. Avoiding gratuitous coverage, the lens takes in the interiors with exactly judicious captures achieved by Le Saux's camerawork which enriches every scene of the film with its automatic grace in movement and deep aesthetics in framing.

Perhaps the most bravura and executively challlenging of the sequences, ensues as a pair of lovers, who couldn't sustain their togetherness on the plains, journey to sun-kissed hills where their love-making is illustrated with the eye of a top artist. John Adams' agile orchestra and panting violins are expertly calibrated to highlight the throes of bare lovers as they carnally celebrate. Imaging, in an inspired move, cuts between scenes of nature and the au naturelle rapture of their bodies. Making love, has rarely if ever been touched upon with such a unreservedly intense yet deeply artistic vision.

Memorable characters pepper the feast. Old Europe is assaulted by post-colonial forces out to claim more than just revenge. The gent who proposes to take over the Recchi textile business, is a smooth-talking, insufferable new-age-philosophy-spouting young mogul who is given the ridiculously exotic name Shai Kubelkian (Waris Ahluwalia hamming it up in a icily calm way). His preposterous, softly stated 'wisdom', and flawless engagement with the ladies of his acquisitioned house, is something we may contrast with the no-nonsense stewardship of Ida (Maria Paiato). Guadagnino's formibadle marshalling of his roster-full of resources is reflecting even in the detailing of this minor character particularly in the finale. Throughout the movie, she remains a tidily attired, solidly built, assiduously working pillar of emotional support for the family when they need a shoulder to cry on and someone to talk to , apart from the round-the-clock upkeep of that demanding estate.

As the epicenter of this movie's flux, Emma as protrayed by Tilda Swinton is a landmark example of atypical casting. In a superbly understated performace , there is vulnerability, a genuinely tender heart and innate grace in her layered portrayal. As the middle-aged mistress of the house who was transplanted decades ago to this very rich family, Emma remains polite, sincere and down-to-earth, gaining trust and acceptance of its insiders. The opening sequence is a splendid synecdoche of her temperament. Though she is the queen of the mansion, she calmly and keenly attends to the planning of the momentous family dinner thus showing her commitment to the nitty-gritties. At the dinner when her father-in-law (who is fond of her) makes a good-natured jab at his grand-son,she looks at her ward with a special blended expression of amusement and sympathy that does not go overboard. To mollify her daughter for whom the rest of the family also claps in sympathetic encouragement, she holds and kisses her and then with delicacy and feeling utters some words inaudible to us, in a fashion uncannily similar to how the "royals" make seemingly involved small-talk with the ballboys-'n'-girls in Wimbledon pre-match ceremonies. Towards the end when grieving Emma, her formal gown unchanged, slumps into bed in a small spartan room set away from the rest of the grand house, and Ida wakes her up next morning with a gentle 'You have to get up' and Emma slowly awakens with a beleaguered face, throughout this ordeal there is never any forceful sorrow displayed yet it is easy to sense the deep ache in her bones and soul.

Swinton is slim and tall - two definite physical assets but she's not an automatic choice for a leading lady as we've known from her previous films. This is where director Guadagnino's perspectives are telling - he says : " I think beauty is a very overrated concept. In particular what is overrated is the idea that beauty comes objectively. From this perspective I'm not interested in it at all. And I'm definitely not interested in style. I'm interested in form, in the shape of things. And in commitment to the degree of never letting go the quest for the meaning of things. That can come off as beauty and style, but that's not where I start from."

Pic : (L) Director Luca Guadagnino , (M) Maria Berenson , (R) Tilda Swinton

.jpg)

Why does Emma make that (to use a polite sophisticated word) "crazy" choice to throw away everything - respect, family, huge wealth, societal approval - just to follow a call of the heart? If she actually decides to stay on with her new-found lover, she will be in her seventies when he is in his fifties. It may be plainly stated that Emma belongs to that category of ladies, of less than one in hundred, who have the capacity to make a choice, greatly damaging to so many people, so late in their lives because their heart never got old; it has remained dangerously young and devoid of the circuitry that makes the usual brain such a safe place. The other vital answer is that she is a construct of director Guadagnino - a man who has led the kind of life he has, knows very well the savage price one pays for being true to heart.

Other critics have carped that the penultimate phase of the film descends into stereotypical melodrama. Yes it does - an uncomfortable situation partially resolved by an extreme turn of events, with grieving thereafter. Even here Guadagnino is perhaps slyly offering a play of contrasts as if to say - yes, this is your bit of standard-issue TV soap with its familiar suds and tears - only to show us in the ensuing phase which is the finale how he takes the same template of melodrama and launches it into the empyrean.

It starts with a preamble piece in a high-ceiling church superbly informed by silence from the composer. The usually prim and elegant Emma, now devastated, has never looked more miserable than she is made to look in that damp cathedral. The orchestra then magnificently rears up for the next part of the finisher back in the mansion - a finale that dazzlingly blends cinema with opera. The course of events is pretty simple but is directed with monumental vision. Frenetic physical movement is married to an earthquake of detachment as a life-altering decision is quickly made. A lady places her hand on her heart and looks at her misty-eyed daughter - there are no words but we sense what is being advised. Ida weeps grievously and we feel her crushing sorrow. There is a swooping movement onto an empty carpet and thence to those grand glass doors which are now ajar...

Even the textured canvas which fills the screen to carry the end credits, is a work of art.

Incredibly, there is inserted an epilogue of sorts, lasting only a few moments, set in a cave - akin to a vaguely savoury wholly out-of-place tidbit at the end of a show-stopping dessert. It's as though Guadagnino looked back to see the enormity of what he had achieved and then decided in a demented nebulous state of mind to besmirch a corner of the canvas at the end.

But that matters little. What remains towering is a work the aesthetics of which can proudly establish entry into the international textbook of how to make a film. And on a personal level, lo Sono L'Amore will last as an elegant anatomic detailing of that invisible weapon of mass destruction called love.

UPN

UPNWORLD welcomes your comments.

0 COMMENTS

WRITE COMMENT